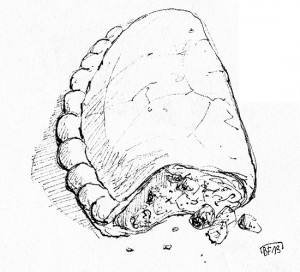

Cornish pasties

Something touched my face. I was aware of light through my eyelids but would not open my eyes for fear of what I should see. A hand was lifting me. I could visualize it – gnarled and black, more beast-like than human – and screamed again. Then a voice quietening me, calling my name:

‘Jane … are you all right? There’s nothing to be frightened of. I promise you.’

Andrew’s voice. I opened my eyes. In the light of the miner’s lantern I saw him bending over me. I whispered:

‘Another dream?’

He shook his head. ‘No dream. You are safe now.’

He helped me to my feet, and as he did I clung to him, putting my head against his chest. I still could not believe it. He would vanish and I would be left in blackness. I wanted one thing, but desperately – that before that happened he would kiss me. It was all I needed, but the need was an agony.

Gently he disengaged me from him. I hated that, but knew anything he did was right. And I knew at last he was really beside me, and no ghost. He said:

He took a flask from his pocket, and put it to my lips. I drank obediently, choking on the fiery liquor. My eyes were streaming, and he gave me a handkerchief to wipe them. ‘Now water.’ He produced another flask, and I drank from it greedily. ‘And food, of a kind. Only a couple of cold pasties, but better than nothing.’

The cook at Carmaliot made Cornish pasties for the men when they were working away from home. They were a labourer’s diet, originally a frugal preparation for the miners to take underground with them. I had never eaten one before: one did not find them in Portsmouth and it was unthinkable in Cornwall to serve them to the gentry. But I never recalled tasting anything in my life as good. While I ate Andrew watched me. His face, shadowed in the lamplight, was much like I had seen it that first day on the moor, with a stubble of beard, dark brown glinting coppery red. And yet it was so different. How could I have thought those blue eyes hard?