Like a rat in a drain

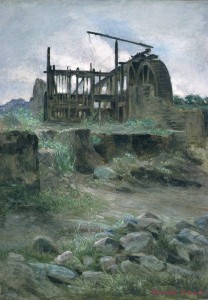

I had already noticed a small hill rising out of the rolling contour of the moor, and now saw a building huddled beside it, or the ruin of one. It was low-lying, with a shattered slate roof that left much of its interior open to the heavens. I wondered, as we covered the remaining distance, what merit of interest it might have to justify his bringing me to see it. But at least there was no more talk of me and Michael: we rode in silence.

Close by the building John dismounted, and helped me down. The walls were of blue granite, solid still, but the window spaces held only the rotting remains of wooden frames. I looked inside and saw bareness: stone walls, a floor invaded by heather and grasses. I asked him:

‘What was it used for? A dwelling – so far out on the moor?’

‘Not a dwelling. It is an abandoned tin-mine. Or rather the surface part – the place where stores, picks and shovels and all that, were kept. The mine itself is on the other side.’

He led the way and I followed, puzzled still. The country hereabouts, I knew, was dotted with similar relics. It scarcely seemed worthwhile to come so far, riding double, to see one. John indicated the hill.

‘That was the tip for waste material. The ore was taken away on pack-horses to be treated, but of course they were obliged to bring out a great deal of useless rubble as well. Hundreds of tons of it.’

‘It must have been abandoned long ago – it is almost completely overgrown.’

‘Nature has her kindnesses as well as cruelties. See, here is the shaft.’

It was surmounted by the remains of a superstructure. I saw a rusting iron wheel, weathered wood, and ropes dangling down into blackness. The shaft was square, about five feet across, the top of it rimmed with cracked granite paving stones. John picked up a loose chip, and tossed it in the hole.

‘Listen.’

I strained my ears and heard a dull plop from the depths.

‘Deep for these parts,’ John said. ‘A hundred feet I should say, at least.’

For all the warmth of the day, I found myself shivering. He said:

‘And water at the bottom, as you can hear. It was probably flooding which made them abandon the working. There was one mine, over towards Bodmin, where a dozen tinners were drowned, following a cloud-burst. Think of it – scrabbling down there like a rat in the earth, and then dying like a rat in a drain. It is not a pretty picture.’